Student Behavior & Teacher Turnover in Post-pandemic Classrooms

Student Behavior & Teacher Turnover in Post-pandemic Classrooms

December 2024

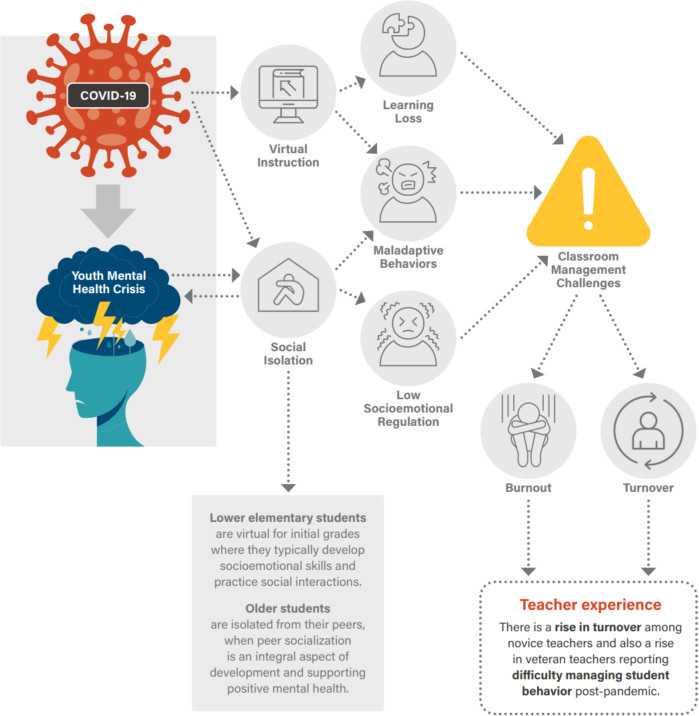

Reports of children with mental health issues and maladaptive behaviors increased following the unprecedented pandemic-era events.i Since returning to in-person instruction, teachers are concerned by an uptick in these issues,ii including a decline in students’ respect for authority, lower tolerance for redirection, a rise in misbehaviors, fighting, and swearing in schools.iii iv Teachers now identify managing student behaviors as one of their two largest job-related stressors (along with attending to pandemic-era learning loss).v vi Working in this environment can cause chronic stress, eventually leading to teacher burnout and eventual turnover.vii Studies before the pandemic show that the stress of dealing with student maladaptive behaviorsviii and heightened disciplinary issues can increase the likelihood that a teacher will leave their position.ix

In the years following the pandemic, Virginia teachers who left their positions identified inadequate support and ineffective leadership as two of the largest contributing factors to their decision.x Divisions across Virginia and the nation continue to struggle with persistent teacher turnover and are taking note of such important contributing factors. This brief summarizes the research on student behavior issues connected to teacher turnover and points education leaders toward solutions supported by evidence-based practices.

Causes of Teacher Turnover

Many teachers feel that they do not possess the appropriate skill sets to address their students’ new behavioral needs.xi These added demands contribute to higher rates of burnout and teacher turnover. The antecedents that influence maladaptive behaviors and teacher turnover are factors within a complex web of school interactions, which are depicted in the map below.

Mental Health Issues

Mental health among children and teenagers declined during the pandemic.xii About 44% of teenagers nationally reported feeling persistently sad or hopeless during the pandemic, an increase of four percentage points from 2019 to 2020.xiii These adverse effects seem to be more pronounced for girls, LGBQT+ youth, and children who have experienced racism.xiv

Socialization and Socioemotional Regulation

Teachers and administrators report a noticeable deterioration in students’ emotional regulation since returning to in-person instruction.xv xvi Students typically develop socioemotional and peer socialization skills during the early grade levels.xvii However, students who were virtual during these years missed the opportunity to learn these foundational skills. In addition, peer socialization is a significant component of adolescent development, which was inhibited by social distancing.xviii

Teacher Burnout

Teachers are tasked with the difficult job of improving student academic achievement while also addressing the youth mental health crisis and socioemotional difficulties that cause many of their students to display maladaptive behaviors. Spending more time on maladaptive behaviors inhibits educators’ ability to teach and address learning loss. As a result, teachers leaving the classroom spiked during and after the pandemicxix ranging from half a percentage point to nearly five percentage points across states where COVID-era teacher turnover was studied.xx xxi xxii While these statistics may seem miniscule, each percentage point represents thousands of teachers across each state.

To illustrate this point using Virginia, the Commonwealth had 1,063 unfilled staffing positions in the 2019-2020 SY, which jumped to 3,649 vacancies for the 2023-2024 SY.xxiii Region 4 alone had over 1,000 unfilled vacancies for the 2023-2024 SY.xxiv Increased turnover occurs throughout the distribution of experience of teachers, with just as many late-career teachers leaving as early-career teachers.xxv High turnover throughout the teacher workforce is a cause for concern. Veteran teachers possess human capital; their experience and knowledge can be used to develop early-career teachers. At the same time, those early-career teachers are the future of the workforce. Thus, their retention is vital to the stability of the teacher workforce.

Evidence-Based Solutions

There are evidence-based practices that teachers and school leaders can implement to address student maladaptive behaviors to improve classroom management and decrease teacher burnout. However, research about students’ behavior in schools post-COVID is only beginning to emerge. The research presented below includes pre-pandemic studies that focus on these issues and that attempted to isolate the influence of student behavior on teacher turnover within the school environment.

Addressing Trauma and Students' Mental Health

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a trauma-informed approach to identifying and supporting students’ mental health after the pandemic.xxvi This means providing all students with a routine, structured environment with caring adults and freeing up time to identify and screen for students who may be struggling with mental health issues. Trauma-informed pedagogy promotes a classroom culture emphasizing a safe and structured environment where behavioral expectations are clearly outlined, acknowledging the impact of adverse life experiences.xxvii xxviii The structure of trauma-informed classrooms resembles the Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS) classroom structure, with which many schools in Virginia are already familiar. Therefore, classrooms already using PBIS to fidelity could easily adopt a traumainformed approach.

One randomized controlled trial examined the effects of integrating mental health professionals into a PBIS framework using the PBIS Interconnected Systems Framework (PBIS-ISF). The schools included in this study were those identified as already using PBIS school-wide to fidelity.xxix Fidelity is necessary because PBIS develops systematic routines and expectations to promote self-efficacy in students. PBIS-ISF uses community-based partnerships - such as mental health professionals - to support students’ social, emotional, behavioral, and academic needs with focused attention on supporting students’ mental health.xxx In this study, community-based partnerships included mental health professionals placed within the schools and schools collaborating with mental health centers within the community. The six PBIS-ISF schools experienced about a 0.50 standard deviation decrease in office discipline referrals.xxxi To understand what this effect would look like in Virginia, consider one county in Region 4 that counted 4,924 incidences of behaviors disrupting the classroom in the 2022-2023 SY. A decrease by 0.50 standard deviations would mean a decrease of 156 referrals. While the sample of this study was small, only six schools in the treatment group and 18 in the control group, it does offer some preliminary evidence to address students’ mental health. The study suggests adjusting systems schools already have in place, such as partnerships with community organizations, can help students struggling with mental health issues that negatively impact their experience in the classroom.

Some divisions have already begun creating mental health networks for students. For example, Fairfax County offers free telehealth for high school studentsxxxii and Loudoun County offers free resources for mental health assessments and services for children and families on their division website.xxxiii Indeed, pre-pandemic research found telehealth was effective at diagnosing and improving the behavioral health of children and teens.xxxiv

In addition to school-wide support systems, it is also crucial for students to build relationships within school that provide emotional support. A nationally representative survey conducted by the CDC on adolescent mental health during the pandemic found that students with a strong personal connection at school - either an adult or a peer - had better mental health outcomes. For students who can identify feeling close to someone at school, only 28.4% identified poor mental health in the past 30 days, compared to 45.2% for those who did not have someone.xxxv In addition, 5.8% of students with close connections at school considered suicide compared to 11.9% of those who did not.xxxvi Increasing connectedness with individuals in their home, school, or community can foster improved mental health in students.

Implementing Curriculum That Builds Social Skills

Teachers also report that students have lower socioemotional regulation since returning from the pandemic. Schools might consider implementing lessons explicitly teaching social skills to reduce maladaptive behaviors resulting from lower emotional regulation. These programs are primarily beneficial in lower elementary grades, where socioemotional development largely takes place. One randomized controlled trial examined the effect of integrating the PurposeFull People curriculum into PBIS Tier-1 instruction on students’ social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes. Researchers observed students who received the program and found that they had a lower rate of incidences of maladaptive behaviors compared to their pre-treatment observations, and they were also 1.5 times less likely to have been disciplined in the last four months than peers who did not receive the PurposeFull lessons.xxxvii

Supporting Teachers’ Behavioral Management Decisions and Their Development

Student behaviors and academic needs will take time to improve. However, teachers in crisis need support now.xxxviii Survey responses from a nationally representative sample of teachers found that teachers who felt their administrators supported their discipline decisions and felt a sense of belonging in their schools were about ten percentage points less likely to experience negative well-being or report constant job-related stress.xxxix Indeed, it seems that supportive systems and teacher well-being are closely connected. Another survey conducted during the pandemic found that teachers who maintained positive well-being identified strong relationships with teachers’ peers and supportive school leaders as the largest contributing factor to their satisfaction.xl In a survey focused on the Virginia teacher labor force, 32% of teachers stated they would consider returning to the profession if there were better systems for managing student behavior in place, and another 30% of teachers would consider returning if there was better support for teachers from their schools and the communities they serve.xli These findings suggest that, similarly to how teachers build a sense of belonging in their classroom to engage students, administrators must make connections and build a sense of belonging for teachers.xlii

Novice teachers typically find classroom management one of the most challenging tasks of the job. The uptick in maladaptive behaviors means new educators are facing more challenging classrooms in their first years. This has resulted in novice teachers reporting lower self-efficacy regarding managing behavior and a rise in turnover amongst them.xliii xliv xlv To mitigate this issue, Prince William County recently implemented a new mentor program for all novice teachers. Each teacher is matched with a mentor teacher in their first year who provides routine feedback and support to their mentees. As teachers progress into their second and third years, they are provided with a mentor to reach out to if needed but are no longer required to have routine meetings. As a result of this new program, the county has seen a 91% retention rate among novice teachers. Other counties might consider similar systems of support to develop their novice educators. Another study found that schools where teachers received more in-person observations had fewer referrals for student misbehavior and fewer suspensions. In their study, the researchers found that increased observations improved classroom management, which administrator presence in the classroom alone could not account for.xlvi This suggests that increasing the number of observations allowed administrators to provide teachers with meaningful feedback that helped teachers improve their classroom management skills, resulting in lower rates of misbehavior. This study highlights that increased observations, feedback, or effective PD that addresses teacher concerns and offers explicit solutions to classroom management can be an effective intervention for teachers struggling with classroom management. This, in turn, could increase teacher self-efficacy and reduce burnout and turnover.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic drastically changed school structure and opportunities to socialize with peers. In addition, some families experienced stress or traumatic events such as a parent losing their job or the loss or illness of a loved one. In Virginia, in the first year of the pandemic, the death rate rose 15% higher than expected levels, and countrywide, over 1 million lives were lost. This has lasting effects on the mental health and socioemotional skills of children and adolescents. Therefore, schools should continue promoting classroom culture, emphasizing safe and structured environments where behavioral expectations are clearly outlined, and screening for and providing mental health services to those who need them. Schools would benefit from teachers explicitly teaching social skills in lower grades, especially for cohorts who attended lower elementary grades virtually and missed the opportunity to socialize with peers and develop these skills. Finally, teachers need supportive environments from peers and administrators as they navigate this difficult moment in education. Administrators should build relationships with their teachers and provide collaborative time for teachers to build relationships with each other. Teachers would also benefit from direct support or explicit training to help improve classroom management skills and address these new behavioral challenges.

If your school or district is interested in adopting or adapting one of the interventions presented, or if your organization has implemented the intervention discussed without realizing the expected benefits, EdPolicyForward welcomes the opportunity to problem solve collaboratively. Please reach out to us at epf@gmu.edu.

- Patrick, S.W., Henkhaus, L.E., Zickafoose, J.S., Lovell, K., Halvorson, A., Loch, S.L., Letterir, M., & Davis, M.M. (2020). Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey. Pediatrics, 146(4). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-016824

- National Center for Education and Statistics. (2022, June 6). More than 80 percent of U.S. public schools report pandemic has negatively impacted student behavior and socio-emotional development. https://nces.ed.gov/whatsnew/press_releases/07_06_2022.asp

- Oxley, L., Asbury, K., & Kim, L.E. (2023). The impact of student conduct problems on teacher wellbeing following the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. British Educational Research Journal, 50(1), 200-217. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3923

- Welsh, R.O. (2022). School discipline in the age of COVID-19: Exploring patterns, policy, and practice considerations. Peabody Journal of Education, 97(3), 291-308. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2022.2079885

- Doan, S., Steiner, E.D., Pandey, R., & Woo, A. (2023). Teacher well-being and intentions to leave: Findings from the 2023 state of the American teacher survey. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1108-8.html

- Jimenez, K. (12, June 2023). Behavior vs. books: US students are rowdier than ever post-COVID. How’s a teacher to teach? USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/education/2023/06/12/us-schools-seebehavioral-issues-climb-post-covid/70263874007/

- Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammon, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters and what we can do about it. Learning Policy Institute.

- Tsoulopous, C.N., Carson, R.L., Matthews, R., Grawitch, M.J., & Barber, L.K. (2010). Exploring the association between teachers’ perceived student misbehavior and emotional exhaustion: The importance of teacher efficacy beliefs and emotion regulation. Educational Psychology, 30(2), 173-189. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01443410903494460

- Allensworth, E., Ponisciak, S., & Mazzeo, C. (2009). The schools teachers leave: Teacher mobility in Chicago Public Schools. Consortium on Chicago School Research at the University of Chicago Urban Education Institute. https://consortium.uchicago.edu/sites/default/files/2018-10/CCSR_Teacher_Mobility.pdf

- Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commisson. (2023). Virginia’s K-12 teacher pipeline (Report 576). https://jlarc.virginia.gov/pdfs/reports/Rpt576-3.pdf

- Barnum, M. (27, June 2023). The teaching profession is facing a post-pandemic crisis. Chalkbeat. https://www.chalkbeat.org/2023/6/27/23774375/teachers-turnoverattrition-quitting-morale-burnout-pandemic-crisis-covid/

- Patrick, S.W., Henkhaus, L.E., Zickafoose, J.S., Lovell, K., Halvorson, A., Loch, S.L., Letterir, M., & Davis, M.M. (2020). Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey. Pediatrics, 146(4). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-016824

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2011-2021. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/yrbs_data_summary_and_trends.htm

- Abrams, Z. (1, January 2023). Kid’s mental health is in crisis. Here’s what psychologists are doing to help. American Psychological Association, 54(1), 63. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2023/01/trends-improvingyouth-mental-health

- Jimenez, K. (12, June 2023). Behavior vs. books: US students are rowdier than ever post-COVID. How’s a teacher to teach? USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/education/2023/06/12/us-schools-seebehavioral-issues-climb-post-covid/70263874007/

- Oxley, L., Asbury, K., Kim, L.E. (2023). The impact of student conduct problems on teacher wellbeing following the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. British Educational Research Journal, 50(1), 200-217. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3923

- Egan, S.M., Pope, J., Moloney, M., Hoyne, C., & Beatty, C. (2021). Missing early education and care during the pandemic: The socio-emotional impact of the COVID-19 crisis on young children. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49, 925-932. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01193-2

- Magis-Weinberg, L., Arreola Vargas, M., Carrizales, A., Thanh Trinh, C., Munoz Lopez, D., Hussong, A.M., & Lansford, J.E. (2024). The impact of COVID-19 on the peer relationships of adolescents around the world: A rapid systematic review. Journal of Research on Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12931

- Camp, A., Zamarro, G., & McGee, J. (2023). Looking back and moving forward: COVID-19’s impact on the teacher labor market and implications for the future. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 1-27. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737241258184

- Bacher-Hicks, A., Chi, O., & Orellana, A. (2023). Two years later: How COVID-19 has shaped the teacher workforce. Educational Researcher, 52(4), 219-220. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X231153659

- Bastian, K.C., & Fuller, S.C. (2023). Educator attrition and mobility during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educational Researcher, 52(3), 516-520. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X231187890

- Goldhaber, D., & Theobald., R. (2023). Teacher turnover three years into the pandemic era: Evidence from Washington State (Brief No. 32-0223). Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research. https://caldercenter.org/publications/teacher-turnoverthree-years-pandemic-era-evidence-washington-state

- Virginia Department of Education. (2022). Turning the tide: A strategic plan to address the educator shortage. https://www.doe.virginia.gov/teaching-learningassessment/teaching-in-virginia/turning-the-tide

- Virginia Department of Education. (2024). Education Workforce Data and Reports. https://www.doe.virginia.gov/teaching-learning-assessment/teaching-in-virginia/education-workforce-data-reports

- Bastian, K.C., & Fuller, S.C. (2023). Educator attrition and mobility during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educational Researcher, 52(3), 516-520. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X231187890

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2022). Interim guidance on supporting the emotional and behavioral health needs of children, adolescents, and families during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/ clinical-guidance/interim-guidance-on-supportingthe-emotional-and-behavioral-health-needs-ofchildren-adolescents-and-families-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/?_ga=2.239558976.2146354611.1720534087-337788334.1720534087

- Cavanaugh, B. (2016) Trauma-informed classrooms and schools. Beyond Behavior, 25(2), 41-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/107429561602500206

- Pickens, I.B., & Tchopp, N. (2017). Trauma-informed classrooms. National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. https://www.wyschoolpsych.org/wp-content/uploads/NCJFCJ_SJP_Trauma_Informed_Classrooms_Final7213.pdf

- Weist, M.D., Splett, J.W., Halliday, C.A., Gage, N.A., Seaman, M.A., Perkins, K.A., Perales, K., Miller, E., Collins, D., & DiSefano, C. (2022). A randomized controlled trial on the interconnected systems framework for school mental health and PBIS: Focus on proximal variables and school discipline. Journal of School Psychology, 94, 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2022.08.002

- Center on PBIS (2024). Mental health/soci-emotional behavioral well-being. https://www.pbis.org/mental-healthsocial-emotional-well-being

- Weist, M.D., Splett, J.W., Halliday, C.A., Gage, N.A., Seaman, M.A., Perkins, K.A., Perales, K., Miller, E., Collins, D., & DiSefano, C. (2022). A randomized controlled trial on the interconnected systems framework for school mental health and PBIS: Focus on proximal variables and school discipline. Journal of School Psychology, 94, 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2022.08.002

- Fairfax County Public Schools. (2024). Mental Health Care for All High School Students. https://www.fcps.edu/teletherapy

- Loudoun County Public Schools. (2024). https://www.lcps.org/

- Hilty, D.M., Ferrer, D.C., Parish, M.B., Johnston, B., Callahan, E.J., & Yellowlees, P.M. (2013). The effectiveness of telemental health: A 2013 review. Telemedicine and e-Health, 19(6), 444-454. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3662387/

- Jones, S.E., Ethier, K.A., Hertz, M., DeGue, S., Le, V.D., Throton, J., Lim, C., Dittus, P.J., Gede, S. (2022). Mental health, suicidality, and the connectedness among high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic-Adolescent behaviors and experiences survey, United States, JanuaryJune 2021. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 71(3), 16-21. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/su/su7103a3.htm

- Jones, S.E., Ethier, K.A., Hertz, M., DeGue, S., Le, V.D., Throton, J., Lim, C., Dittus, P.J., Gede, S. (2022). Mental health, suicidality, and the connectedness among high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic-Adolescent behaviors and experiences survey, United States, JanuaryJune 2021. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 71(3), 16-21. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/su/su7103a3.htm

- Zhang, Y., Cook., C., & Smith, B. (2023). PurposeFullPeople SEL and character education program: A cluster randomized trial in schools implementing tier 1 PBIS with fidelity. School Mental Health: A Multidisciplinary Research and Practice Journal, 15(3), 985-1002. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-023-09600-2

- Naff, D.B., Williams, S., Furman, J., Lee, M. (2020). Supporting student mental health during and after COVID-19. Virginia Commonwealth University: Metropolitan Educational Research Consortium. https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/merc_pubs/112/

- Steiner, E.D., Woo, A., Suryavanshi, A., Redding, C. (2023). Working conditions related to positive teacher wellbeing vary across states: Findings from the 2022 learning together survey. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA827-15.html

- Doan, S., Steiner, E.D., Pandey, R., & Woo, A. (2023). Teacher well-being and intentions to leave: Findings from the 2023 state of the American teacher survey. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1108-8.html

- Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission. (2023). Virginia’s K-12 teacher pipeline (Report 576). https://jlarc.virginia.gov/pdfs/reports/Rpt576-3.pdf

- Frahm, M., & Cianca, M. (2021). Will they stay or will they go? Leadership behaviors that increase teacher retention in rural schools. The Rural Educator, 42(3). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1335408.pdf

- Bacher-Hicks, A., Chi, O., & Orellana, A. (2023). Two years later: How COVID-19 has shaped the teacher workforce. Educational Researcher, 52(4), 219-220. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X231153659

- Goldhaber, D., & Theobald., R. (2023). Teacher turnover three years into the pandemic era: Evidence from Washington State (Brief No. 32-0223). Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research. https://caldercenter.org/publications/teacher-turnoverthree-years-pandemic-era-evidence-washington-state

- VanLone, J., Pansé-Barone, C., & Long, K. (2022). Teacher preparation and the COVID-19 disruption: Understanding the impact and implications for novice teachers. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 3, 100-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2021.100120

- Hunter, S.B., Kho, A., Bowser, K.M. (2023). Policyassigned teacher observations, their implementation, and student discipline outcomes: Main, mediated, and moderated relationships. TN Education Research Alliance. https://cdn.vanderbilt.edu/vu-sub/wp-content/uploads/sites/280/2023/12/14183036/tera-workingpaperhunter-231214.pdf

This brief is the third of a series sponsored by a partnership between George Mason University’s Center for Advancing Human-Machine Partnerships and EdPolicyForward, the Center for Education Policy at Mason’s College of Education and Human Development. We wish to thank the educators in Northern Virginia who reviewed and offered their feedback on this brief. If you would like more information, please visit our website at: https://cehd.gmu.edu/centers/edpolicyforward/.